Close Read Join or Die What Advantages Do the French- American Colonies

On May 9, 1751, Benjamin Franklin published a satirical commodity in the Pennsylvania Gazette commenting on British laws that allowed bedevilled felons to be shipped to the American colonies. Every bit an equal merchandise, Franklin wryly suggested that the colonists should send rattlesnakes to Nifty Great britain and advisedly distribute them among "Places of Pleasure."[1] Although these reptiles seemed to be the well-nigh suitable returns, Franklin nonetheless lamented on one disadvantage of the trade. In Franklin's mind, fifty-fifty if Great britain received these venomous pests, the risk was non comparable to the one the colonists' bore. Co-ordinate to Franklin, "the RattleSnake gives Warning before he attempts his Mischief; which the Captive does non."[2] Even so his sardonic wit, this American entrepreneur did not know that he would eventually unleash a literary rattlesnake upon Britain and its American colonies. Precisely three years later, on May 9, 1754, Franklin published a political cartoon depicting a rattlesnake with the admonishing title, "JOIN, or DIE."[3]

This graphic masterpiece, originally representing the inevitable death of the American colonies if they failed to unite during the impending French and Indian War, after stirred political and religious controversy between Loyalists and Patriots during the American Revolution. To Loyalists, the snake represented Satan, deception, and the spiritual fall of man, proving the treachery of revolutionary thought. To Patriots nevertheless, the serpent depicted wisdom, vigor, and cohesiveness, especially when the colonies united for a common purpose. By closely examining colonial newspapers and images, one notices that Franklin's drawing not simply represented the political unity of the American colonies, but evoked religious ideals during the Revolution. Newspaper articles adopted the infamous words, "JOIN, or Die!" to stir colonial citizens to join the revolutionary crusade, renditions of Franklin'south drawing were published on mastheads of newspapers, and conflicting editorials were published to teach the correct religious estimation of the "American Serpent."[4] Due to the cartoon'due south prominent influence and the controversy that information technology created, the snake inevitably became the first national symbol for the newly created U.s.. Loyalists and Patriots eventually synthesized biblical imagery with Franklin'southward political drawing to articulate their positions for the revolutionary cause, creating religious controversy while solidifying the serpent as America'due south starting time national emblem. This is an intriguing subject that has received piffling analysis, requiring further investigation.[v]

Birth of the Snake Cartoon

To fully appreciate the political and religious controversy that Benjamin Franklin's snake cartoon generated, it is of import to first relate the history of the illustration equally well as discuss the symbolism that Franklin hoped it would portray. Past reexamining some historical details, it is possible to show how the political history and religious story of Franklin'southward drawing are inherently linked.

During early May 1754, when England and France competed for territory in the Ohio River Valley, Benjamin Franklin was a staunch advocate for British colonial unity. Writing an article in his newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, Franklin reported the tragedy of Ens. Edward Ward'due south give up to Capt. Claude-Pierre Pecaudy. He wrote that Ward's troops, while trying to build an English fort in the area of modern-24-hour interval Pittsburgh, were surrounded past Pecaudy's French strength of over four hundred men.[6] And then later describing the hardships the colonists would suffer if the French continued to seize Pennsylvania's western territory, Franklin inserted his ophidian cartoon. Displaying a rattlesnake cut into eight parts, the forewarning phrase "JOIN, or DIE." loomed below the epitome.[seven] This illustration, equally scholar J.A. Leo Lemay asserted, was the offset published symbol for colonial unity.[8]

In addition, as Lemay revealed, this probably was not a foreign image to some English language citizens. The ophidian was a classical symbol and had been presented in religious and mythological literature for centuries. Lemay wrote, "Franklin knew the various symbolic meanings of the ophidian, and when he wanted to portray colonial union, he recalled the image of a snake cut into 2 that appeared in a seventeenth-century keepsake book."[ix] This book was Nicolas Verrien's Recueil d'emblemes, displaying a cut snake with the motto, "'Un Serpent coupé en deux. Se rejoindre ou mourir' (A snake cutting in two. Either join or die)."[10] Besides, throughout the years a superstition had widely circulated among the British colonies that a cutting snake would come live if the pieces were joined back together before sundown. This also may have been another influence to assistance Franklin concoct the cartoon.[eleven] Franklin most likely knew about the French snake emblem and the mythological folklore behind the snake. Some of his readers, no doubt, would have been familiar with these representations as well.

It is no surprise, therefore, that Franklin'due south image apace became a popular symbol for colonial unity. Four colonial newspapers published versions of the drawing in May 1754, with the near dramatic modification past the Boston Gazette on May 21.[12] Although the drawing exhibited the motto "JOIN or Die," the image of the snake was more detailed, displaying a roll with the proverb, "Unite and Conquer."[thirteen] Franklin's drawing became a reoccurring symbol during the upcoming months, especially when The Virginia Gazette reported the defeat of Col. George Washington's forces at Fort Necessity. The commodity concluded by referencing the cartoon, stating, "Surely this will remove the infatuation of security that seems to have prevailed too much among the other colonies" and "inforce [sic] a late ingenious Emblem worthy of their Attention and Consideration."[xiv] Inside a brusk menses of time, colonials started to appreciate Franklin's cartoon. Individuals, whether interpreting the snake emblematically or superstitiously, understood its message — if the colonies did not unite to defend themselves against foreign encroachments, they would perish and become discipline to other nations. Although Franklin's drawing became a pop symbol before the French and Indian War, it would not go a national emblem until the American Revolution.

Revolutionary Resurrection

To scholars such as J.A. Leo Lemay and Gordon Southward. Wood, Benjamin Franklin's snake drawing ultimately became a national keepsake due to its unifying aspects and powerful political imagery. These historians are correct to assert that the cartoon encapsulated the political and social struggles of the American Revolution, especially when Britain began enforcing new taxation laws on its North American colonies. However, the story turns much more captivating when reading the newspaper editorials.[fifteen] By examining these writings within the political context of the fourth dimension, a fascinating history emerges. Franklin'south cartoon was resurrected as a potent call for colonial unity against Slap-up Britain, ultimately giving momentum to the religious controversy that would soon follow when Loyalists and Patriots began writing their opinions on what the snake symbolized.

Once word reached the colonies that Parliament passed the Stamp Act in March 1765, a surge of protests spread throughout the continent. The lieutenant governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson, feared for his life, and lamented to Franklin virtually the mobocracy that was forming in Boston.[16] The home and role of Massachusetts' stamp distributor was attacked, and Hutchinson'southward mansion was invaded. These acts fabricated Hutchinson promise for a speedy repeal of the tax, just as Franklin suggested in a private letter of the alphabet, this was not likely to happen. Hutchinson besides informed Franklin how Bostonians protested the new tax.[17]

According to Hutchinson, opponents resurrected Franklin's motto, "JOIN, or DIE" to promote their insurgency. He wrote to Franklin, "When you and I were at Albany ten years ago, we did not Suggest an spousal relationship for such Purposes as these."[18] Franklin had published his snake cartoon two months before he and Hutchinson met at the Albany Congress in July 1754 to endeavor to course an intercolonial regime under British authority. Franklin's cartoon had been originally intended to support this type of marriage under the British Crown.[19] But a decade later, aroused colonists started to use Franklin's cartoon to encourage unification against United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland's encroachments, transforming the original intention of the epitome by making it a phone call for revolutionary ideology. Hutchinson recognized the significance of this transformation, and as others would later realize overtime, Franklin'southward cartoon would radically influence revolutionary protests.

When Parliament passed the Boston Port Deed at the end of March 1774, riots swept the urban center and other colonies lent moral and economical support to Boston.[20] Every bit the act declared, Boston's harbor was closed on June 15, 1774 and was expected to be tightly regulated until the E Bharat Company received compensation for the merchandise that was lost during the Boston Tea Party.[21] This act outraged several colonists and induced them to further adopt Franklin'southward famous motto. With the admonishing championship, "JOIN OR Die," Rhode Island's Newport Mercury published an commodity that rebuked Parliament and declared that the American colonies needed to unite. The article stated:

The act of parliament for blockading the harbour of Boston, in society to reduce its spirited inhabitants to the most servile and mean compliances ever attempted to be imposed on a free people, is allowed to be infinitely more alarming and dangerous to our common liberties, than fifty-fifty that hydra the Postage stamp Act (which was destroyed by our firmness and union) and must be read with a glowing indignation by every real friend of freedom, in Europe and America – … The Generals of despotism are now drawing the lines of circumvallation around our bulwarks of liberty, and aught just unity, resolution, and perseverance, tin save ourselves and posterity from what is worse than death – SLAVERY. [22]

Parliament'southward acts were seen by aroused colonists as reducing Bostonians to a form of slavery, and if the colonies did not unite, these insurgents claimed that every province would soon be subjected to tyranny. Franklin's motto at present became imbedded in revolutionary ideology and began to exemplify the crusade. A rendition of this article was printed in The Massachusetts Spy on May 26, 1774, demonstrating that the forewarning title, "Join OR Dice" continued to spread throughout the colonies.

One calendar month later, Franklin's motto once again appeared in the Newport Mercury, this time promoting the unification of the colonies to create a Continental Congress. On June 27, 1774, the paper reported:

The freeholders and inhabitants of New Bailiwick of jersey, had a meeting at Newark in said country, the 11th of June inst. when they passed resolves nearly like to those of nigh other towns and colonies on the continent, and were very zealous for having a congress appointed, equally soon as possible; and co-ordinate to present appearances such a congress will certainly take place … notwithstanding the enemies of American freedom, in this town and other places, have boasted that the other colonies would not bring together the province of Massachusetts Bay. The colonies know they must 'JOIN or DIE.' [23]

As the article claimed, in that location were individuals who boasted that the colonies would not unify for the revolutionary cause. Notwithstanding as this Patriot alleged, a congress was beingness summoned for that very purpose. This commodity demonstrated the tensions that stirred betwixt Loyalists and Patriots during the tempestuous months of 1774. Colonists of several ideological backgrounds began to contemplate their political views, and many resolved to determine which side they would support. This year, known for the Intolerable Acts that were imposed on the colonies, is when Franklin's cartoon became the apotheosis of the revolutionary cause and aroused the almost heated controversy. This is when Franklin'due south drawing would begin to be synthesized with biblical literature, affixing it a religious icon and America's first national keepsake.

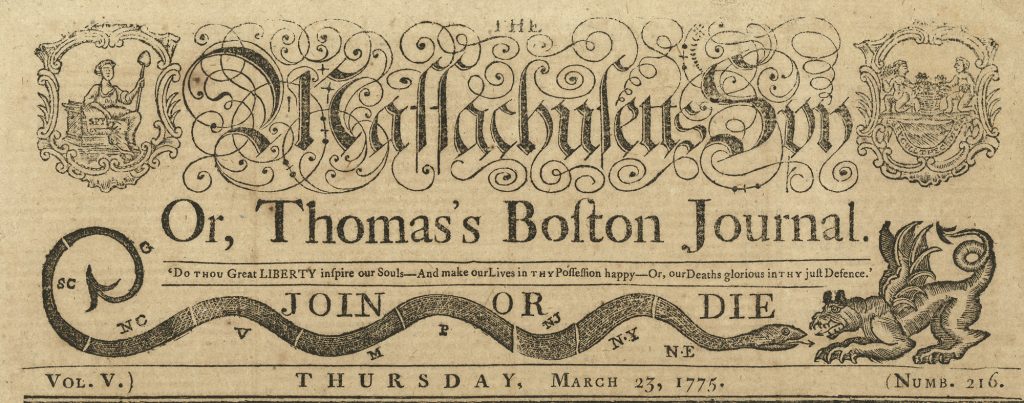

By July 1774, several colonial newspapers placed renditions of Franklin's drawing on their mastheads. The New-York Journal displayed an image of a snake cut into 9 parts with the saying "UNITE OR Die."[24] However, the most detailed alteration was created by the Massachusetts Spy. This newspaper already had an ornate masthead, but when it added Franklin'due south prototype, the front end page became a crest for revolutionary fervor. The newspaper displayed a snake separated into nine parts contending with a dragon.[25] This creative version of Franklin's cartoon attempted to portray the competition between the American colonies and Great Britain. The aforementioned motto "JOIN OR Dice" was printed above the snake, but it was accompanied by another adage: "Exercise THOU Dandy Liberty inspire our Souls – And make our Lives in THY Possession happy – Or, our Deaths glorious in THY just Defence [sic]."[26]

Controversy Over the Snake

These mastheads adopted Benjamin Franklin'southward snake cartoon for two purposes: to purport revolutionary credo and to encourage unity confronting Great U.k.. Every bit a result, Loyalists became unsettled and began to synthesize Franklin'southward image with biblical literature to undermine the Patriotic campaign.

The first Loyalist satirization of Franklin'southward cartoon appeared in Rivingston's New York Gazetteer on August 25, 1774. Entitled, "On the SNAKE, depicted at the caput of some American NEWS PAPERS.," the epigram read:

YE Sons of Sedition, how comes it to pass,

That America's typ'd by a Ophidian — in the grass?

Don't you think 'tis a scandalous, saucy reflection,

That merits the soundest, severest Correction,

NEW ENGLAND's the HEAD, too; ——- NEW – ENGLAND'South abused;

For the Head of the Serpent nosotros know should be Bruised. [27]

Adopting linguistic communication from the third chapter of Genesis, the rhyme manipulated the expletive that God had placed on the serpent. Genesis reads, "And I volition put enmity between thee and the woman, and between thy seed and her seed; it shall bruise thy head, and thou shalt bruise his heel."[28] Typifying revolutionary America as a "Snake" and its citizens as "Sons of Sedition," this verse form paralleled God's curse with the inevitable defeat of the colonies. Past combining political ideals with biblical literature, this poem associated revolutionary America with Satan. However, the fact that this author tried to condemn the illustration proves that Franklin's drawing had now become a powerful symbol for colonial unity. This epigram was afterwards reprinted in the Boston News-Letter on September viii, 1774, demonstrating that Loyalist fervor was growing to condemn the revolutionary cause.[29]

Inspired by the Loyalist poem found in Rivington'south New York Gazetteer, a competing rhyme was published in the Patriot newspaper, the New-York Journal, on September 1, 1774. With the heading, "For the New-York Journal. On reading the Lines in Mr. Rivington's concluding Paper, on the Snake at the Head of several American News Papers, the following occurred, viz.," the poem read:

Ye Traitors! The Serpent ye with Wonder behold,

Is not the Deceiver then famous of old;

Nor is information technology the Snake in the Grass that ye view,

Which would be a striking Resemblance of you,

Who aiming your Stings at your Country'southward Heel,

Its Weight and Resentment to crush you lot should feel. [thirty]

Referencing the aforementioned biblical poesy of the previous Loyalist epigram, this anonymous Patriot author associated Loyalists with the treachery of Satan. Past equating Loyalist fervor to "Stings" aimed at the colonies' "Heel," the writer used the same biblical story to declare that the Patriots would "crush" any Loyalist backfire. Using religious imagery, this Patriot hoped to highlight the literary power of Franklin'due south cartoon. Also, by publishing this poem in a newspaper that proudly displayed a rendition of the epitome on its masthead, the writer tried to convince Patriotic readers that the revolutionary cause was sacred.

In the same issue of the New-York Journal, some other Patriot article appeared to explain Franklin'southward drawing. Although the editor claimed that the piece was written "about ii or three months" earlier the current edition, he stated that he was not reminded of information technology until the first Loyalist poem was published in Rivington'southward New York Gazetteer.[31] The writer, known but as "SPECULATOR," introduced the article past stating that he hoped to explicate "the Design of the emblematical Figure at the Caput" of The New-York Journal. [32] The writer wrote, "The Serpent has been from the earliest Ages, used as an Emblem of Wisdom – We are told in the tertiary Affiliate of Genesis, that the Serpent was more subtil than any Beast of the Field, and the Apostle exhorts us to exist wise every bit Serpents."[33] Instead of associating the serpent with Satan, this author linked Franklin'south cartoon to positive religious connotations. Referencing the third chapter of Genesis in beneficial terms, this article once more combated Rivington's Loyalist editorial which had drawn upon the aforementioned biblical affiliate. Also, past referencing the tenth chapter of Matthew, the writer associated Franklin's cartoon with the words of Jesus Christ, which read, "Behold, I send y'all forth as sheep in the midst of wolves: be ye therefore wise every bit serpents, and harmless as doves."[34] The religious connotations the Patriot author related to Franklin's cartoon were virtuous and emulated the teachings of the Christian savior. Past synthesizing Franklin's cartoon with biblical virtues, the author demonstrated that the snake was a selection emblem for the revolutionary entrada. The writer also stated that the ophidian represented "Life and Vigour," as well equally "a watchful Dragon" that guarded the colonists' "Rights and Liberties."[35]

After The New-York Journal published its Patriot rebuttals, the Boston Mail Boy decided to join the debate and reprinted a satirical poem found in the London Magazine. On September 26, 1774, the newspaper published the following:

A BOSTONIAN EPIGRAM.

To the Ministry building

YOU'VE sent a Rod to Massachusetts,

Thinking the Americans will kiss it;

But much I fear, for Britain's Sake,

That this same Rod may testify a Snake. [36]

Referencing the fourth chapter of Exodus, this poem drew upon the imagery of God transforming Moses' rod into a serpent.[37] In the story, God used the transformation of the rod as a warning and example of his ability. Notwithstanding what makes this epigram and then intriguing is that it characterized the British ministry as Moses, who when showtime experiencing the transformation of his rod, became afraid.[38] When the British Crown imposed the Intolerable Acts, it hoped to suppress the colonists into obedience. However, every bit the verse form suggested, instead of this "rod" convincing Americans to respect British power, the rod turned into a ophidian, showing the Crown that it needed to be mindful of its actions.

Every bit the poem alleged, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland's repressive deportment created the American snake, making the Crown face serious consequences. This epigram direct referenced Franklin's cartoon, but information technology also helped solidify the epitome of the serpent every bit a symbol for revolutionary thought. The serpent was not portrayed as a symbol of evil, but as a retribution for Britain's harsh treatment. Franklin'due south prototype was used equally an keepsake of power and it cast a moral light upon the Patriotic cause. Past giving this image religious and ethical overtones, Patriots hoped to demonstrate that their ideology was righteous; they wanted Franklin'southward cartoon to represent the virtue of God's holy word.

Since Franklin'south drawing had started to get a hallowed emblem, Loyalists connected to write manufactures hoping to undermine its Patriotic symbolism. In an article published by the Norwich Packet on Oct half dozen, 1774, Samuel Peters, a well-known reverend and Loyalist, complained about the persecution inflicted by the Sons of Liberty and continued this activity with Franklin'southward cartoon. Peters wrote, "The Riots and Mobs that have attended me and my House, set on by the Go_ _ _ _ _ _ of Connecticut, take compelled me to have upward my Abode hither; and the Clergy of Connecticut must fall a Sacrifice with several Churches, very soon, to the Rage of Puritan Mobility, if the Old Serpent, that Dragon, is not bound."[39] Peters attached the satanic connotation of Franklin's serpent cartoon to Patriots, simply referring to them as "the Old Ophidian, that Dragon." In his article, Peters insinuated that Patriots were possessed by the devil and that the revolutionary cause needed to be "spring." Peters non just referenced the biblical image of Satan, but applied circumlocution establish in the start two verses of chapter twenty in the volume of Revelation. The verses read, "And I saw an affections come down from heaven, having the key of the bottomless pit and a great chain in his hand. And he laid hold on the dragon, that old serpent, which is the Devil, and Satan, and spring him a thousand years."[xl] Alluding to this scripture, Peters attempted to demonstrate the sinful country of Patriots.

Equally the years progressed, Loyalists connected to write commentaries that rebuked American Patriots. Samuel Peters, also equally others, proceeded to link Franklin's cartoon to the evils of Satan.[41] By consistently synthesizing negative biblical imagery with Franklin's illustration, yet, they unwittingly solidified the drawing every bit a venerated Patriotic emblem and provoked revolutionaries to redeem their reputations. Patriots continued to attack Loyalist propaganda by publishing their own writings, and by applying positive religious imagery with Franklin's cartoon, they fabricated the snake a virtuous symbol of their entrada.

When the fall of 1774 arrived, colonial condescension of British authorization was imbedded in Massachusetts. Even so, as Loyalist compositions connected to be printed, Patriots persisted with their countercharges. Magnifying the importance of Franklin'south ophidian as a religious and Patriotic keepsake, an epigram published in the Massachusetts Spy advanced the editorial campaign. Entitled, "On the BRITISH Ministry, and NEW-ENGLAND, the Head of the American Snake. AN EPIGRAM, 1774," the verse form read:

BRITAIN'southward sons line the coast of Atlantic all o'er,

Great of length, merely in latitude they now wind on a shore.

That's divided past inlets, past creeks, and by bays, –

A Snake* cut in parts, a pat keepsake conveys –

The cruel junto at home – sure their heads are merely froth –

Fain this snake would have caught to supply viper broth

For their worn constitutions – and to it they go,

Hurry Tom, without hearing his yes or his no,

On the boldest adventures their register can show:

Past their wisdom advised, he their courage displays,

For they seized on the tongue 'mong their first of essays;

Nor once thought of teeth when our Serpent they assail –

Though the prudent catch Snakes by the dorsum or the tail –

To direct to the caput! our good King must indite 'em –

They forgot that the head would nearly certainly bite 'em. [42]

The rhyme suggested that Loyalists, while trying to curb Patriots from promoting their cause, forgot that the American serpent had metaphorical "teeth" that could "seize with teeth" them. These "teeth" were the poems and articles that Patriots continued to publish to refute Loyalists that branded revolutionary ideology as evil. This epigram, although using common snake imagery, besides independent religious symbolism, referencing several passages from the Bible. Using words such as "wisdom" and "head" to reference the American snake, the writer evoked imagery from the books of Genesis and Matthew, equally well every bit others throughout scripture.[43] Furthermore, by stating that the American snake was going to "bite" the jerky British Crown, the author noted the political tensions that existed in the colonies. Franklin's serpent, which began as a political phone call for colonial unity, had now get a religious embodiment of the American Revolution.

By continuing to reference Benjamin Franklin's ophidian drawing, Patriots and Loyalists increased its literary power. However, information technology might seem odd that the man who created the cartoon and who was known for his contributions to journalism, would remain silent during this widely publicized controversy. Franklin was an ardent Patriot for the revolutionary cause, and as the creator of the cartoon, he surely would have known what the paradigm symbolized. Therefore, in a style that was common for Franklin, he surreptitiously joined the editorial contest by submitting an article to the Pennsylvania Journal.

On December 27, 1775, using the pseudonym "An American Guesser," he published an article entitled, "The Rattle-Serpent as a Symbol of America."[44] With a whimsical tone, he wrote that his wishes were "to guess what could take been intended by this uncommon device."[45] Franklin penned: "I took care, however, to consult on this occasion a person who is acquainted with heraldry, from whom I learned, that it is a rule among the learned in that science 'That the worthy backdrop of the creature, in the crest-built-in, shall be considered,' and, 'That the base ones cannot have been intended;' he too informed me that the antients considered the snake as an emblem of wisdom, and in a certain attitude of endless elapsing – both which circumstances I suppose may have been had in view."[46] Interestingly enough, Franklin wrote that people of ancient times had recognized the serpent as an emblem of "wisdom" and "countless duration." Similar to Patriots who countered Loyalist editorials, Franklin related the serpent to positive ancient writings, which of course, included biblical literature. This is not surprising. Later on all, co-ordinate to historian Thomas Southward. Kidd, Franklin had constantly referenced the Bible to back up his ideas and arguments. "Franklin knew the Bible backward and forwards," Kidd affirmed. "Information technology framed the mode he spoke and idea. Biblical phrases are ubiquitous in Franklin'southward vast body of writings. Even as he embraced religious doubts, the King James Bible colored his ideas about morality, human nature, and the purpose of life. It served as his well-nigh common source of similes and anecdotes. He even enjoyed preying on friends' ignorance of scripture in society to play jokes on them."[47] Franklin was wide in his assertion, but when he connected the serpent to ancient notions of "wisdom" and "endless duration," he probably referenced the books of Matthew and Numbers. As previously stated, in the book of Matthew, Jesus Christ had declared that men should exist wise equally serpents. In the book of Numbers, the story of the brazen snake conveyed the allegory of timeless duration. To heal the ancient Israelites who had suffered from ophidian bites every bit a punishment for their sin and unbelief, God had commanded Moses to arts and crafts a "fiery" or brass serpent and fasten information technology to a pole. All the Israelites had to practise to receive healing was cast their eyes on the ophidian. Later on, many Christians interpreted this story as a foreshadowing of Christ's atonement for mankind — Jesus had died for the sins of the world so that people could look on him to receive eternal life.[48] Simply like Moses'south brazen serpent which represented extended life, Franklin suggested that the rattlesnake symbolized the vigor of the American colonies. If Patriots continued to seek what the snake drawing exemplified, Franklin subtly insinuated, the Revolution would endure.

Determination

As the Revolutionary State of war dragged on, Benjamin Franklin's serpent cartoon continued to part as America'due south holy national symbol. In an article published past The New-Hampshire Gazette on March nine, 1779, a journalist wrote, "The British King of beasts, unable to trample to any purpose the head of the American Serpent is at present playing with its tail."[49] Reporting the southern campaign of the British ground forces, this newspaper again represented the colonies as a serpent with biblical connotations. However, as the state of war drew closer to an end, the image of the American serpent prodigal. The bald eagle became the new national emblem in 1782, forever replacing Franklin's political and religious illustration that had gained its prominence during the American Revolution.[50]

The image of the American serpent was kickoff conceived by Franklin in 1754, so contested by Loyalists and Patriots from 1774 to 1779.[51] All the same through this controversy, the cartoon became a political and religious ensign. Loyalists represented the snake equally a symbol of evil, while Patriots endowed the snake with honorable qualities. All these allusions came from biblical literature — literature which carried divine ascendancy for justifying the political positions of both parties. By synthesizing Franklin's ophidian drawing with religious imagery, the illustration became not just a call for colonial unity, but a holy embodiment of the American Revolution. As The New-Hampshire Gazette claimed, Great Britain could non bruise the caput of the revolutionary campaign, and like to Moses lifting the brazen serpent to the ancient Israelites, so too did Patriots raise Franklin'due south snake during the Revolution, calling for colonists to "Bring together, OR Dice."

[one] Editorial, "Rattle-Snakes for Felons," Pennsylvania Gazette, May 9, 1751.

[two] Ibid.

[iii] Benjamin Franklin, editorial, Pennsylvania Gazette, May 9, 1754. Although some historians question whether Franklin's original cartoon displayed a rattlesnake, J.A. Leo Lemay conjectures that this was probably Franklin's intention. Also, by referencing rattlesnakes in his manufactures published by the Pennsylvania Gazette (May 9, 1751) and The Pennsylvania Journal (December 27, 1775), information technology seems likely that Franklin meant for the drawing to portray this type of serpent.

[4] Editorial, "Extract of a letter from New London, Feb. 27, 1779," The New-Hampshire Gazette, March 9, 1779. See too, editorial, "Boston, March iv," The New Jersey Gazette, March 31, 1779.

[5] The most comprehensive examination of Franklin's snake cartoon was written by Albert Matthews in his article, "The Serpent Devices, 1754-1776, and the Constitutional Courant, 1765," Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts xi (1910): 408-453. However, Matthews' commodity is more than of a bibliographic discourse, and he did not examine the religious connotations constitute in Loyalist and Patriot editorials.

[6] J.A. Leo Lemay, The Life of Benjamin Franklin: Soldier, Scientist, and Politico 1748-1757 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 3: 363.

[7] Ibid.

[eight] Ibid., 3: 364.

[9] Ibid., 3: 367.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid. Run into also Donald Dewey, The Fine art of Sick Will: The Story of American Political Cartoons (New York: New York Academy Press, 2008), two.

[12] For examples of these renditions, run into Matthews, "The Snake Devices," 416-17.

[xiii] Editorial, Boston Gazette, May 21, 1754.

[fourteen] Quoted in Lemay, The Life of Benjamin Franklin, 3: 366.

[fifteen] See Lemay, The Life of Benjamin Franklin, three:362-368; Gordon South. Wood, The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin (New York: Penguin Press, 2004) 110.

[xvi] Forest, The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin, 110.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Quoted in ibid.

[19] Thomas S. Kidd, Benjamin Franklin: The Religious Life of a Founding Male parent (New Oasis, CT: Yale Academy Press, 2017), 180-81.

[20] Robert Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (New York: Oxford Academy Press), 237-twoscore.

[21] Ibid., 355.

[22] Editorial, "Bring together OR Dice!" The Newport Mercury, May 16, 1774. Meet likewise editorial, "Bring together OR Die!" The Massachusetts Spy, May 26, 1774.

[23] "NEWPORT, JUNE 27," The Newport Mercury, June 27, 1774.

[24] Masthead, The New-York Journal, July 7, 1774.

[25] Masthead, The Massachusetts Spy, October six, 1774.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Epigram, Rivington's New-York Gazetteer, August 25, 1774.

[28] Genesis 3:fifteen.

[29] Epigram, "On the Snake, depicted at the Head of some American NEWS PAPERS," The Boston News-Letter, September eight, 1774.

[thirty] Epigram, "For the NEW-YORK JOURNAL. On reading the Lines in Mr. Rivington's last Newspaper, on the Serpent at the Caput of several American News Papers, the post-obit occurred, viz." The New-York Journal, September 1, 1774.

[31] SPECULATOR, editorial, "The following Slice was written about two or 3 Months agone, but laid aside and forgot, till brought to Remembrance by some Lines in Mr. Rivingston's last Paper. TO THE PRINTER. July i, 1774," The New-York Journal, September 1, 1774.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Matthew 10:sixteen.

[35] SPECULATOR, editorial, The New-York Journal, September i, 1774.

[36] Epigram, "From the LONDON MAGAZINE, for June, 1774. A BOSTONIAN EPIGRAM. To the Ministry." Boston Postal service Male child, September 26, 1774.

[37] Exodus 4:3.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Samuel Peters, editorial, "BOSTON, October ane, 1774," Norwich Packet, October vi, 1774.

[40] Revelation 20:1-2.

[41] For further examples of Loyalist editorials and propaganda, see too Editorial, "BOSTON. MASSACHUSETTS continu'd. To the INHABITANTS of the Province of MASSACHUSETTS-BAY." The New-Hampshire Gazette, March 10, 1775; Editorial, "Parnassian Parcel," Essex Journal, March 22, 1775; Verse form, "(Continued from our last.)" Essex Journal, May six, 1775; LEONATUS, Editorial, "LONDON, From the General Evening Post, of Baronial 5, 1777. To the EDITOR." The New-York Gazette, Nov 3, 1777.

[42] Poem, "Parnassian Parcel." The Massachusetts Spy, October 27, 1774.

[43] See Genesis 49:17, Numbers 21:vi-9, Psalms 140:3, and Jeremiah viii:17.

[44] Benjamin Franklin (AN AMERICAN GUESSER), "The Rattle-Ophidian as a Symbol of America," The Pennsylvania Journal, December 27, 1775.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Kidd, Benjamin Franklin: The Religious Life, v-half dozen.

[48] Numbers 21:four-9; John Wesley, Wesley's Notes on the Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library, n.d.), 905.

[49] Article, "Extract of a letter of the alphabet from New London, February 27, 1779," The New-Hampshire Gazette, March 9, 1779; See also, Commodity, "Boston, March 4." The New Jersey Gazette, March 31, 1779.

[50] Lemay, The Life of Benjamin Franklin, 650, footnote 34.

[51] It seems that 1779 was the concluding yr when Franklin'due south cartoon was referenced using religious connotations. However, further research could potentially uncover more than articles, editorials, epigrams, and poems that continued Franklin's snake to biblical literature. Nonetheless, the controversial climax between Loyalist and Patriots occurred between 1774-1775.

Close Read Join or Die What Advantages Do the French- American Colonies

Source: https://allthingsliberty.com/2018/01/join-die-political-religious-controversy-franklins-snake-cartoon/

0 Response to "Close Read Join or Die What Advantages Do the French- American Colonies"

Post a Comment